The last two weeks, we explored how cortisol is often oversimplified as “the stress hormone,” spiking in moments of intense “fight or flight” survival instincts. The usual example is the caveman being chased by a lion. While that metaphor isn’t wrong, it misses key points about how cortisol actually works and why it’s still widely misunderstood.

One major distinction is the difference between acute and sustained stress. Cortisol is meant for short-term challenges like escaping danger, finishing a tough workout, or waking up in the morning. But in modern life, the body often faces sustained moderate stress like emails, traffic, financial pressure, and emotional strain that keeps cortisol signaling active without ebbs and flows. Research shows that it’s not necessarily “high cortisol” that’s harmful, but the constant drip of sustained stress that creates dysregulation.

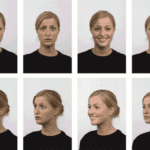

Additionally, calling cortisol the “fight or flight” hormone is an oversimplification. It rises during acute threat, but many other stress mediators are at play, like adrenaline, norepinephrine, and inflammatory cytokines. Cortisol isn’t always about fight or flight either; more recent studies have shown that some people, particularly many women, display a “fawn and tend” stress pattern. Animal and human research has found that “bullying” can lower cortisol for the bully by displacing stress to someone else. This shows that stress regulation is a social process, not just a hormonal one.

Physical Effects and Myths About Cortisol

Wellness marketing has capitalized on cortisol’s link to stress and weight gain, creating the impression that “high cortisol” directly causes fat accumulation, fatigue, and burnout. In reality, cortisol is one of many stress signals, not a standalone culprit.

Cortisol spikes actually raise metabolic rate in the short term for quick energy. However, when stress is prolonged, the body starts interpreting this as a need to conserve energy. Combined with stress-induced eating (driven by reward hormones like dopamine), this can shift metabolism into storage mode rather than burn mode.

Cortisol itself does not directly cause weight gain — instead, it influences where fat is stored. Chronically elevated cortisol favors visceral fat around internal organs, creating the classic “round belly with thinner limbs” appearance. Outside of rare medical conditions like Addison’s disease or Cushing’s syndrome, there’s no single marker that defines “high or low cortisol” in healthy people.

The “cortisol imbalance” concept is a marketing gray area — because cortisol can be too high or too low and still create overlapping effects like fatigue, brain fog, and disrupted sleep. High cortisol may promote fat storage and anxiety; low cortisol may cause salt cravings, dizziness, and low motivation. Both can distrupt blood pressure, thyroid function, blood sugar, inflammation, and immune resilience. These are real physical patterns, but they don’t always map neatly to a single hormone level.

The key takeaway: irregular cortisol patterns are a stress flag. Managing cortisol levels won’t affect a dysregulated stress response, but addressing the entire system and root causes will usually bring cortisol release back to functioning in its usual pattern.

Maintaining Cortisol Balance

Before paying for expensive lab testing — which often requires multiple daily samples over weeks to be meaningful — most people benefit more from restoring basic stress rhythms than chasing supplement fixes. Rather than adding cortisol to the list of things to stress about, there are common-sense solutions that not only help with cortisol but stress management as a whole.

Quality sleep and light exposure will help to start balancing an overactive or depleted stress response. Commonly, we experience “wired and tired,” which is an overstimulated fatigue. This usually comes with too much screen time and stimulants and not enough physical activity to get to sleep.

For diet, there are some habits that support the body’s ability to regulate stress, as well as habits that create perceived stress. Eating balanced, warm meals signals safety while skipping meals signals stress. Coffee before eating or too much caffeine will signal stress. Alcohol before bed stresses the system and interferes with sleep, which will create a physical stress response. Vitamins and minerals from food sources like Vitamin Bs, Vitamin Cs, Magnesium, Zinc, and Omega-3’s are all multi-functional stabilizers.

Lastly, the psychological research on how cortisol affects our thinking points to the significance of sustained stress. We often don’t manage it because it doesn’t look like “trauma,” but it weighs heavily over time. In today’s world, we often don’t have control or autonomy over a lot of circumstances. Meditation is often encouraged as a way to unwind, but cortisol studies suggest outlets that boost confidence may help stabilize cortisol from creating “bullies”.

Ultimately, focusing on cortisol alone won’t fix dysregulated stress patterns — but healthy rhythms, emotional regulation, and lifestyle recovery will bring cortisol back into balance as a result. When your environment feels safer, your hormones follow suit.