Last week, we covered some common misconceptions about the “stress hormone” we call cortisol. This week, we’ll look at several intriguing studies that explore how sustained stress negatively impacts our cognitive ability and overall health.

During stress, the connection between the thalamus and amygdala becomes more excitable. This allows sensory information to be processed faster — useful for quick decisions — but it reduces the accuracy of interpretation. The amygdala, a part of the brain that helps retain memories related to danger, becomes especially active under stress. Cortisol strengthens the amygdala’s role in remembering fear, making those memories last longer. When a traumatic event becomes a long-term memory, it can act as a persistent trigger.

Additionally, stress decreases the function of the prefrontal cortex, making it more difficult to forget a fearful experience — or even the general feeling of fear that manifests as anxiety. The combination of an overactive amygdala and a slowed prefrontal cortex means that fear associations form more easily and last longer under stress. This interplay helps explain many of the behavioral patterns observed in studies on both humans and animals.

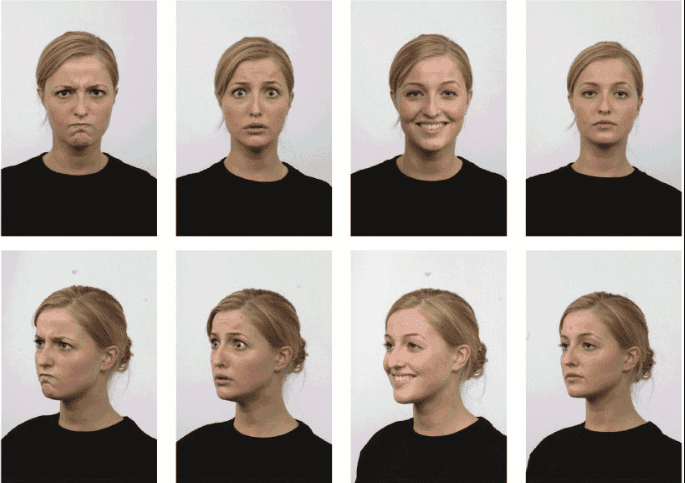

One clear example of cortisol’s impact on the brain’s recognition abilities is in how people interpret facial expressions. Sustained stress makes individuals spend more time focusing on angry faces. In studies where cortisol was administered via injection, participants interpreted facial expressions with less accuracy.

Animal studies reveal even more about cortisol’s role in social behavior. For instance, mice are naturally empathetic — a mouse will have a lower pain threshold if its cagemate is in pain. However, this empathy does not extend to unfamiliar mice. Interestingly, when researchers blocked cortisol production in stressed mice, the animals showed the same level of “pain empathy” toward unfamiliar mice as they did toward familiar ones.

Cortisol has also been studied in human gambling behavior. People under stress — such as from sleep deprivation — tend to take bigger risks, a fact well known to casinos. Severe stress pushes both men and women toward greater risk-taking, but moderate stress has gender-specific effects: it tends to make men more risk-seeking, while women become more risk-averse. Even in neutral conditions, men on average are more comfortable with risk than women. This suggests that stress and cortisol don’t necessarily change behavior, but rather amplify existing tendencies.

Cortisol also influences what researchers call stress displacement. When cortisol levels rise and stress is sustained, people (and animals) often redirect their frustration onto others. For example, when stressed rats are given several options to reduce stress — such as food or running on a wheel — their preferred coping mechanism is to bite another rat. Among baboons, nearly half of violent incidents occur when a losing male displaces aggression onto a lower-ranking female. Remarkably, this secondary aggression lowers cortisol levels in the aggressor, reinforcing the behavior.

Unfortunately, we see similar patterns in humans. One study found that when a major football team loses, domestic partner violence in the surrounding area increases by 10%. There is no significant change when the team wins or was expected to lose. However, as the stakes rise, so does the violence: a playoff loss raises rates by 13%, and losing to a rival team raises them by 20%.

Sustained stress creates complex physiological and behavioral responses that go far beyond cortisol alone. Still, cortisol remains a consistent factor — spiking in stressful moments and shaping responses such as risk-taking, reduced empathy, and displaced aggression.