The following article is a 3:00 read

Last week, we covered that any somatic exercise is built on the theory that emotions create physical stress. Somatic therapies use physical practices in order to alleviate physical discomfort and emotional release, or stress reduction. These practices focus on using the somatic nervous system (conscious and intentional movement) to restore well-being.

Rolfing:

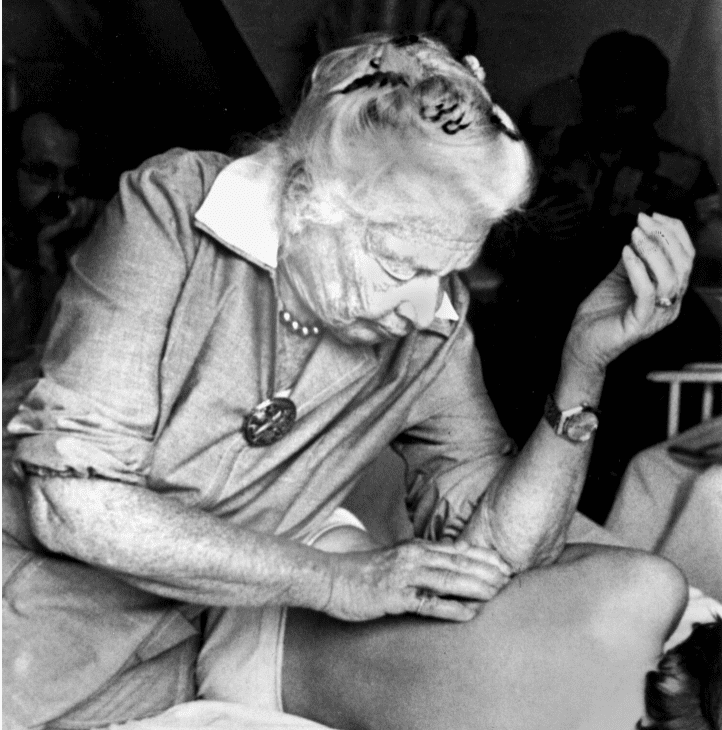

Most people hear about Rolfing through referrals from physical therapists, chiropractors, or other practitioners addressing physical issues. Word-of-mouth often describes Rolfing as a deep-tissue, sometimes uncomfortable massage that targets trigger points but usually results in relief from physical discomfort. Some clients also report emotional release or reduced anxiety, though this is less commonly emphasized. Mainstream medical sources, such as Wikipedia and various health reviews, note that Rolfing has little scientific evidence backing its claims and often classify it as pseudoscience.

Rolfing was developed by Ida Rolf, one of the few women of her era to earn a PhD in biochemistry from Columbia University in 1920. She worked in organic chemistry at the Rockefeller Institute before developing Rolfing, drawing inspiration from healing practices and yoga to help with her own and her son’s pain management.

According to the Rolf Institute of Structural Integration:

“Rolfing is a form of bodywork that reorganizes the connective tissues, called fascia, that permeate the entire body. Dr. Rolf recognized that the body is inherently a system of seamless networks of tissue rather than a collection of separate parts. These connective tissues surround, support, and penetrate all of the muscles, bones, nerves, and organs. Rolfing Structural Integration works on this web-like complex of connective tissues to release, realign, and balance the whole body. Essentially, the Rolfing process enables the body to regain the natural integrity of its form, enhancing postural efficiency and freedom of movement.”

Traditionally, Rolfing is structured as a series of 10 sessions, each addressing different parts of the body in sequence, with optional follow-ups or “tune-ups” afterward.

Breathwork:

Meditation has long been regarded as one of the best practices for mental health, but it can be difficult to maintain without guidance or proper technique. Breathwork, however, has gained traction among both holistic practitioners and mental health professionals as a simple, accessible tool for reducing stress and addressing trauma.

Unlike meditation, which is primarily mental, breathwork directly engages the body and breath, making it a somatic practice. Many professionals highlight its benefits: a calmer state of mind, a shift in the nervous system, and easier access to deeper therapeutic work over time. Breathwork can also be practiced alone, without equipment, and often produces immediate results.

Breathwork is one of the simplest somatic methods: by controlling oxygen and carbon dioxide levels, it shifts the body’s nervous system state (typically from sympathetic “fight-or-flight” toward parasympathetic “rest-and-digest”). Unlike meditation—which may involve visualization and the challenge of quieting thoughts—breathwork relies on structured patterns of breathing, which trigger a direct physiological response.

Here is a quick and simple Breathwork exercise to help reset the week, and can be used anytime during the day to re-align the nervous system.

Diaphragmatic Breathing (a.k.a. “Belly Breathing”)

This basic exercise can produce noticeable calming effects within just a few repetitions, or be practiced for several minutes to deepen focus and relaxation.

Step 1:

Begin the inhale by expanding the lower belly, letting it rise like a balloon.

Step 2:

Continue filling the ribcage, expanding outward in all directions—sides, back, and toward the armpits.

Step 3:

Let the breath rise into the upper chest, lifting the collarbone.

Optional:

Hold briefly, then take one more small sip of air through the nose. Notice any tension, stress, or negative feelings that come up.

Exhale:

Slowly release the air through the nose, allowing the chest to drop, the ribcage to contract, and the abdominal muscles to gently draw inward. Intentionally release mental and physical tension during the exhale.