The following is a 4:30 read using The Guardian and The Lede as primary sources

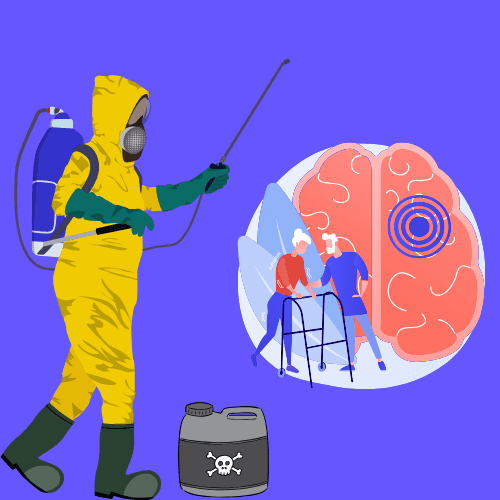

Paraquat is a weed killer that’s been used since the 1950s. An herbicide with similar toxicity issues as the key ingredient in Monsanto’s Roundup (glyphosate), paraquat has undergone decades of testing that have been muddied by corporate agendas. While Europe and most other first-world countries have banned paraquat, the US, India, and China still use it.

In recent years, glyphosate has gotten much more attention as a known carcinogen. Its producer, Monsanto, is a bigger player in US agriculture decisions like the development, use, and labeling of GMOs. As weeds have developed resilience to glyphosate, paraquat has only become a more popular choice in US agriculture. According to The Guardian, the amount of paraquat used in the US has tripled between 1992 and 2018.

The connection between paraquat and Parkinson’s has come under increased scrutiny as the prevalence of Parkinson’s has doubled between 1990 and 2015. While many factors, such as other environmental hazards, genetics, and diet, are also being looked at, it’s been established since the 1970s that paraquat crosses the blood-brain barrier and shows damage to brain cells. It’s a neurotoxin.

Despite the density of research literature that shows that paraquat exposure is a serious risk, Chevron—who used to manufacture and sell paraquat in the US—stated to The Guardian that, “To this day, and despite hundreds of studies being conducted in the past 20 or so years, a causal link between Paraquat and Parkinson’s disease has not been established.”

| The Guardian, in collaboration with The Lege, unearthed a treasure trove of documents that weren’t intended to reach the public. While these documents aren’t enough to show a definitive causal link, they show the concern of leading scientists advising Chevron and other manufacturers of the risks. It also shows these mega-pesticide production companies strong-arming and ultimately selecting who sits on regulatory boards, particularly the EPA.Between 1955–1968, several clinical studies with animals showed that paraquat affects the central nervous system, which is damage connected to Parkinson’s. As paraquat became a popular method for suicide, the autopsies were used as human examples to see the effects of paraquat ingestion. It was found that even with the small amounts of paraquat consumption that would cause a fatality, paraquat accumulated in the deceased’s brain tissue. |

| Internal studies showed paraquat could harm the central nervous system as early as the 1960s–1970s.Chevron and other manufacturers were warned by scientists about possible links to Parkinson’s disease.Companies sought to influence U.S. regulatory decisions, including the EPA’s safety reviews.Documents revealed concern over long-term liability, comparing paraquat risks to asbestos.Despite strong internal warnings, paraquat remained on the market for decades. |

| In the early 1970s, continued animal studies showed that paraquat travels to the brain as well as the spinal cord and lungs. Scientists that were funded by corporate research ran many experiments, which specified that the levels of paraquat found in brain tissue should not be measured. Documents show that in 1974, Chevron gained insider information that the EPA was moving towards banning paraquat. Chevron moved preemptively by adding stronger labels on paraquat, but stood by the stance that as long as goggles and proper safety equipment were used, paraquat was safe to handle. However, within the next two years, concerns ran deeper as reports emerged of field workers with nosebleeds and other signs of central nervous system damage. |

A Chevron lawyer warned the company that there was evidence in a suit that could cost millions of dollars. During this time, correspondence between Chevron, as the seller in America, and ICI, the manufacturer in England, focused on running more trials and mitigating risk factors.

“In October 1985, an internal memorandum circulated to Chevron officials noted that a study by a Canadian researcher had found ‘an extraordinarily high correlation’ between Parkinson’s and the use of pesticides, including paraquat. The memo also noted that paraquat was ‘chemically very similar’ to the byproduct of synthetic heroin called MPTP, which produces almost instant Parkinson’s, by killing dopaminergic neurons in the brain.”

The same memo also points out that Parkinson’s is a slow disease that could cause more financial liability and compares it to selling a product that contains asbestos. A year later, Chevron stopped selling paraquat. Publicly, Chevron has stood by the statement that the decision had nothing to do with safety standards but was simply a financial decision. However, internal documents show personal correspondence between head chairmen that he “could not think of anything more horrible” than to face the consequences of a product that causes a fatal long-term chronic disease, “that may not become apparent except after several years.”

Next week, we will cover the use and industrial selling of paraquat through the 1990s to the present, which is the “post-Chevron” years. As sadly predicted by the Chevron chairman, the consequences of paraquat are a slow disease that takes decades to unfold.