The following is a 3:30 read using The Guardian and The Lede as primary sources

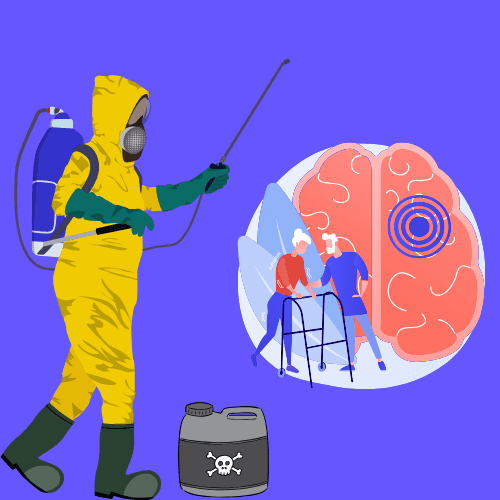

Last week, Pendulum covered how the connection between paraquat and damage to the central nervous system was evident as far back as the 1950s and became scientifically well-established by the 1980s. Yet, reliance on paraquat has only grown since the early 2000s, in part because it received less media scrutiny than its just-as-toxic cousin, Monsanto’s Roundup. Paraquat is equally hazardous, though its manufacturers may have been more effective at suppressing negative publicity.

Even though a substantial body of research had already linked paraquat exposure to neurological harm, studies promoted by the chemical’s producers and sellers worked to muddy the waters. Some of these studies, funded by parties with vested interests, intentionally avoided key indicators, such as paraquat accumulation in the brain. Research released in the 1990’s and early 2000’s often used outdated or less sensitive methods and seemed designed to undercut the strong foundation of existing scientific evidence.

According to The Guardian:

“At the time, the chemical was under regulatory review in Australia and the European Union. The company worried about evolving regulatory policies posing ‘a threat,’ including that regulators may start to replace ‘higher hazard products with lower hazard products,’ and apply a ‘precautionary principle.’

Under that type of regulatory approach, companies seeking to sell a chemical have a burden of proving product safety. In contrast, the U.S. regulatory system largely takes the opposite approach—a chemical must be proven unsafe to be kept off the market.”

At the same time, internal Syngenta scientist Louise Marks found significant brain cell loss in mice exposed to paraquat. However, her findings were withheld from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for 15 years.

The primary victims of paraquat exposure are agricultural workers who come into direct contact with it. While consumers who eat produce sprayed with paraquat ingest microdoses, it’s nearly impossible to trace a direct link between those exposures and Parkinson’s disease. What researchers can track, however, is the rate of Parkinson’s among field workers with documented exposure.

As Chevron board members feared back in the 1970s, paraquat has become the cause of a devastating, slow-progressing, and ultimately fatal illness. This means plaintiffs and their families continue to show up in court for decades. Today, many of the original victims are passing away without ever seeing a final resolution, but their efforts are not dying with them. More and more cases connecting paraquat to Parkinson’s continue to emerge.

The courtroom drama has now stretched on for more than a decade. Many original plaintiffs have seen their conditions deteriorate and have died without receiving justice. And despite growing evidence and ongoing litigation, banning or even regulating paraquat in the U.S. remains an uphill battle. It’s effective, cheap, and tightly woven into the current agricultural economy.